Weight-Loss Strategies

WHEN I WAS A KID, my father was the fattest person I knew. He was 6 feet tall and about 250 pounds, which would've made him the size of an NFL lineman of that era—the early 1960s. If anything, he was proud of his girth. He boasted, "The Marines taught me how to eat," and he spent the rest of his life acting on that knowledge.

Still, it took real effort for a guy to inflate the way my father did. My mother believed he worked harder at eating than he did at his job.

Back then, the average American man in his 30s weighed 170 pounds, so people noticed someone my dad's size. Even in 1980, after we'd joined the same gym, I can remember a conversation with a trainer who said "that guy Gary" was the fattest person he'd seen in a health club. I was one of the skinnier guys, so he didn't realize he had just described my father.

Today you wouldn't notice a man of my father's weight or girth—not when a typical guy in his 30s now weighs 196 pounds. You probably know a few people who would make my dad look svelte. Maybe you're one of them. A lot of us know from sorry experience that the classic weight-reduction formula—exercise more, eat less—works in the short term, but the fat typically comes back. Sometimes a double chin redoubles, just to show you who's in charge.

Human metabolism is a complex system that evolved to keep our weight stable in times of both abundance and famine. How did it devolve into a coin toss where the choices are "heads, you gain weight" and "tails, you gain even more"?

For many, the problem is a condition called metabolic inflexibility, a bit of complicated science that points the way toward simple diet, exercise, and lifestyle modifications—modifications that can help you become lean and stay lean. But before we dive into the deep end of weight-loss research, let's take a quick detour and look at the reasons the single-generation rise in obesity shouldn't have happened. We'll then see how it did happen, and finally we'll reach the important part: how you can seize your own metabolic destiny and steer it toward skinny.

WHY WE CAN'T EAT JUST ONE ANYMORE

From the early 1900s—when obesity was so uncommon that people lined up to gawk at the "fat lady" in circus sideshows—until the 1980s, our per-capita food supply stayed more or less the same.

We could've eaten more food back then. We just didn't crave it as we do now. Consider everything that happens when you eat a normal meal.

- The food you eat becomes progressively less appetizing. No matter how good the first few bites of that steak might be, by the end you're just going through the motions.

- Your stomach expands, sending chemical messages to your brain, asking it to stop eating.

- Your metabolism cranks up as your body works to move the food through your digestive system, burning off 10 percent of the calories you just ate.

- Over the following hours and even days, your body monitors your energy balance—the amount of calories coming in and going out. Eat more than you need and you'll compensate with a faster metabolism—or by burning more calories through physical activity, or by producing more hormones like leptin, which lowers your appetite.

These mechanisms also work in reverse. Should you eat less than you need in order to maintain your current weight, your metabolism slows down to preserve energy, and hunger hormones like ghrelin tick up to increase your appetite.

The goal of this complex system is to hit a balance, at which point it's hard to gain or lose weight. Only powerful stimuli can override this system, to literally alter your metabolism so it can't respond the way it should.

Enter your main adversary: the modern food industry, which is to nutrition what lobbying is to Congress—a sure way to twist a good system into one that runs counter to everybody's best interests.

When Lay's potato chips introduced the famous slogan "Bet you can't eat just one" in the early 1960s, the company knew what it was talking about. Its food scientists were in the process of snipping the brake lines on our appetites, and as a society we began running stop signs that had existed for centuries. The food scientists found ways to combine sugar, salt, and fat so that "enough" was never actually enough. If we have a little, we want a lot. Our metabolism wasn't prepared to counteract the hedonic reward of these new foods or the quantities now available. The food manufacturers ramped up food energy production to 3,900 daily calories per person, enough to put most of us at the "who shrunk my seat belt?" end of the body-weight range.

"Food stimulates many parts of the brain, including regions associated with reward," says Stephan Guyenet, Ph.D., a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Washington and the author of a terrific blog about metabolism and weight control, at wholehealthsource.com. "By stimulating those reward pathways directly, you can have a profound impact on food preference and body fat. Manufacturers are trying to maximize the reward." The upshot, he says: "We're awash in food that's easily available, energy dense, highly palatable, and highly rewarding. Commercial food overstimulates those connections in the brain."

RELATED VIDEO:

SO NOW GLUCOSE IS GETTING US DOWN, TOO

As we eat massive volumes of overstimulating food—the whole tube of Pringles, washed down with an entire Big Gulp—our digestive processes convert it all into massive amounts of blood sugar. That's where the hormone insulin comes in. It's a kind of bodily butler in charge of showing glucose to safe havens in the body. In our society, and in our bodies, it's one overworked butler.

"Your body is hardwired to survive," says Mike T. Nelson, C.S.C.S., a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Minnesota who has studied this problem for the past 6 years. "If your glucose is too high, it's toxic. Your body will do everything possible to get it out of there." The hormone insulin is your main glucose-disposal tool. The longer it stays elevated, the less effective it becomes; and the less effective it becomes, the longer it stays elevated. Insulin's purpose is to eliminate glucose in the blood by storing it in the body. As a consequence, insulin inhibits our ability to burn fat. Chronically elevated insulin means your body is always using less fat for energy than it otherwise would, so fat gathers where you want it least.

Human bodies are designed to run on a mix of fuels, using fat predominantly at rest or during low-intensity exercise. You gradually shift to a higher dependence on carbohydrates as exercise becomes more difficult. If you're metabolically flexible, you can shift easily from one fuel source to the other, tapping into your body's abundant fat deposits while saving those limited carbohydrates for when they're really needed. Someone with chronically elevated insulin becomes inflexible, burning too many carbs all the time and leaving fat stores untouched. That's a metabolic disaster for a body that has more fat than it could ever use—a body that, under normal circumstances, should be tapping fat like a pool of black gold under the tundra. "Systems are trying as hard as they can to cooperate with each other," Nelson says. "But they can't."

WHY MOST MEN CANT JOG THEIR WAY TO THE PROMISED LAND

We all grow hungry when our carbohydrate supplies run down. This is one of our most important survival mechanisms, due to the fact that our brains normally run on pure glucose. We can make glucose from fat, but that's not the easiest way to get it. Our bodies prefer the real thing. So we become ravenously hungry when our glucose supplies suddenly drop. The problem for the metabolically inflexible man is that his supplies are always running low, and his body is always looking for the next food fix. A workout can exacerbate the problem by draining more carbs than the body wants to give up.

So the standard reaction to too much belly—"I have to start jogging"—could actually hurt in two ways. A man who's using the wrong fuel won't get much out of it because of his limited endurance. He could also end up hungrier afterward, as his body panics over depleted glycogen stores.

"You can't burn excess fat without mobilizing it from a fat cell," says Mike Ormsbee, Ph.D., a professor of exercise physiology and sports nutrition at Florida State University. "You have to move it from the fat cells to the blood so you can eventually use it for energy elsewhere."

Strength training offers a workaround for metabolic inflexibility. "Brief, intense activity seems to dump a lot of fat into the bloodstream," says Christopher Scott, PhD., who studies strength training and metabolism at the University of Southern Maine. "I think it's to fuel recovery."

When you do a bout of cardio, the goal is to reach one level of intensity that you can maintain for a long time. And there's only one recovery period, during which you use much less energy than you did while exercising. But when you're recovering from a set of bench presses or squats, you burn more calories: "If you do 12 sets, that's 12 recovery periods," Scott says. That's in addition to the long postworkout recovery period, so your body has a lot of time to be burning fat, as opposed to relatively short periods of using carbohydrates for fuel.

Because strength training is an anaerobic activity—meaning your body burns mostly carbohydrate while you lift—you're burning mostly fat during the recovery period. Moreover, when you leave the weight room, you're burning many more calories than you were before the workout, and you're burning them for hours.

Another argument for strength training—or, really, for any type of exercise in which you alternate hard work with an easier pace—is that you train your body to shift back and forth between fuel sources, making your metabolism more flexible.

WE NOW RETURN TO YOUR REGULARLY SCHEDULED METABOLISM

As important as exercise is—and we'll deal with that later—it runs a distant second to the first change you need to make.

1. CLEAN UP YOUR DIET

"If we came up with a list of 10 things that affect weight loss, 1 through 7 would involve diet and behavior," Scott says. "Then 8, 9, and 10 would cover exercise."

Research shows that just about any mainstream diet regimen can work, as long as you stick to it. My guess, based on experience, is that a diet won't work for you unless it meets two seemingly contradictory standards: it has to be different from what you're doing now, which is to say it restricts the stuff you currently eat too much of. And it has to be something you can live with for the foreseeable future, meaning it has to be based on foods you like and to which you have easy access.

That's where behavior becomes the key to success. "The amount of food you consume is not just the result of conscious processes," Guyenet says. Exposing yourself to highly palatable, superstimulating foods will derail any diet. Nobody has that much willpower.

Three key actions help you build self-control into your diet.

- Prepare and eat most of your meals at home, with minimal added salt and minimal added sugar.

- Prepare foods so they're as close as possible to their natural state: grilled or baked meat, poultry, and fish; eggs however you like them; raw or steamed vegetables; fruit; beans, nuts, or seeds. For simple recipes to make real food taste better, check out MensHeath.com/shortordercook

- Fill half your lunch or dinner plate with lean protein (chicken breast, sirloin steak, scrambled eggs) and half with fiber-rich vegetables. Protein and fiber fill you up fastest and satisfy hunger longest.

It's possible to gain weight from a diet of mostly home-cooked food, especially if it includes a lot of high-calorie, low-fiber starches like bread, pasta, and potatoes. But, like my father, you'd have to work at it.

2. CUT CARBS AND INCREASE PROTEIN

Since a big belly can be a sign of insulin resistance, and insulin resistance manifests functionally as metabolic inflexibility, you will respond best with a lower-carb diet. Even a small decrease in your insulin level will lead to a large increase in fat burning, says Jeff Volek, Ph.D., who studies strength training and nutrition at the University of Connecticut. "Low-carb diets lead to a much greater decrease in fat."

Low-carb doesn't have to mean militantly low-carb. In a yearlong weight-loss study at Stanford, participants assigned to an Atkins-type diet were eating a third of their calories from carbs by the end—more than twice as much as their Atkins-type diet recommended. And they still did better than people assigned to the other diets.

Carbohydrates are less problematic at two times of the day.

- First thing in the morning. Whole-grain carbs, like steel-cut oatmeal, provide an easy-to-access source of glucose for your body and brain.

- Immediately following a workout, when a baked potato helps you refuel and provides a high level of postmeal satiety.

3. DON'T EAT ON THURSDAY. EVER

There's one surefire way to encourage your body to burn stored fat: stop feeding it. Intermittent fasting—going without a meal for 8, 12, or even 24 hours at a time—is an increasingly popular weight-loss tool. "Even people who are metabolically inflexible use fat as fuel during a fast," says Nelson. 'It ramps up all the processes associated with burning fat."

Entry-level fasters should start with modest expectations. Some find it easy to skip breakfast and extend an overnight fast to 12 or more hours. But it works only if you have the discipline to end the fast with real food rather than by hitting the drive-thru. For others, an early dinner works best, but this plan is easily derailed if you find yourself wide awake and starving at midnight.

A better strategy: Shoot for a daily 6-hour break between two substantial meals. Work up to 8 hours from time to time. If you feel better—and many fasters say they do—build up to a single 24-hour fast once a week. If you feel worse (I know I do), stick with a meal/snack schedule built around foods you prepare yourself.

4. NEVER GO JOGGING

"I don't think low-intensity, steady-state exercise is a very effective stand-alone treatment for existing obesity," Guyenet says. Interval exercise—short periods of hard work followed by longer periods of recovery—pushes your body to shift quickly from carbs to fat and back again while boosting your metabolism for hours afterward.

Here are three ways to light a fire.

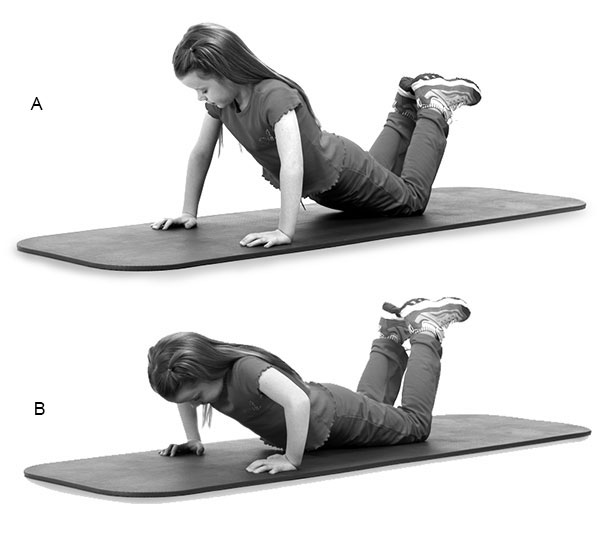

- Time-specific intervals. You might run hard for 20 seconds and then recover for 40 seconds. An advanced athlete might use a 1-to-l work-to-rest ratio, so he'd go hard for 30 seconds and recover for 30 seconds. You can also do this with weights or calisthenics. Ten minutes of these intervals—at the beginning or end of a regular workout or as a stand-alone training session—is plenty to start. Fifteen to 20 minutes is the max for anyone.

- Volume-specific intervals. Go for a fixed number of repetitions if you're lifting (which is how most of us work out), or a specific distance if you're running or swimming, and then recover for however long it takes. You can train like this for a full workout—30 to 45 minutes of lifting or cardiovascular exercise, plus 5 to 10 minutes of warmups.

- Timed volume-specific intervals. You might do 10 pushups or squats or kettlebell swings every minute. The faster you do the reps, the more time you have to recover. But with subsequent sets, your pace will slow down, which cuts into your recovery time and leaves you with more residual fatigue. That's what you want, since fatigue is what keeps your metabolism elevated long after you leave the gym.

5. PUSH BEYOND YOUR COMFORT ZONE

"We want the quick fix, and we want it to be easy," Scott says. "But what do all successful programs have in common? You're working your butt off. Intense activity, by itself, is going to produce changes." That doesn't mean kill yourself every time you pick up a dumbbell. But it does mean pushing your body to do more than it currently does.

"Do more" can mean any of the following:

- Higher volume—more sets, reps, or miles.

- Higher intensity—heavier weights, faster rides or runs.

- Higher frequency—the same thing more often.

- Higher difficulty—more challenging lifts, incorporating hills into cardio training.

From time to time, it helps to ask yourself if what you're doing is "hard" or if you're doing something now that you wouldn't or couldn't do last month, or last year. If the answer is no, you probably need to turn it up a notch (or two).

6. DON'T EXPECT PERFECTION

"Ninety percent compliance is good enough," Nelson says. "The closer you are to 100 percent compliance, the less you benefit from it. An occasional ice cream or Twinkie, or a couple of Ho Hos shouldn't destroy you."

There's one hard-and-fast rule for indulgence, Nelson adds: "Sit back and enjoy it!" Don't feel guilty, don't try to run a marathon the next day just so you can burn it off, and most of all don't gulp down your treat like a junkie who just escaped from court-ordered rehab. The slower you eat, the more you can savor it and the more quickly you'll feel satiated. Then brush your teeth and recommit to your program.

The science of metabolic restoration may be complicated, but the path to success is refreshingly simple: Do the best you can as often as you can, and blame society for the rest.

-

Weird Body Makeover Tip

There are a lot of body makeover tips, strategies and techniques throw

-

Abs Diet Weight Loss Success Story

Name: John Kelly Age: 40 Height: 61 Weight, Week 1: 215 Weight, Week 6

-

STUDY: The Lifting Method That Sky-Rockets Your Metabolism

Push your muscles harder: Using heavier weights may help you blast mor

-

Abs Diet weight loss tips

SUBJECT GUIDELINE Number of meals Six a

-

Your Recipe For Weight Loss Success: Passion: MensHealth.com

Robert Blair nearly died on the ski slopes.

-

Abs Diet: Quick Circuit Workout

Try to squeeze in this 15-minute full-body workout from Mark Philippi,

- DON'T MISS

- The Health Benefits of Eating Full-Fat Cheese

- Have a Threesome, Shed Pounds!

- Belly Off: Rock-Climbing Weight Loss Success Story

- Understand Your Metabolism

- Why Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson Is Technically Obese

- Cooking Weight Loss Success Story

- Eat This, Feel Full, Gain Less

- Weight Loss: Workout Shake

- The Truth about Calories:

- Don’t Fear Fat