"The results were so dramatic that our first instinct was that we had probably mixed up our fly groups and mistakenly looked at young flies," says Girish Melkani, PhD, a co-author of the paper, which was published in Science. "It took many, many rounds of repetitions of the experiments to finally convince us that TRF was responsible for the noticeably younger looking hearts of the chronologically old flies."

These findings add support to the emerging field of chrononutrition—that is, the idea that when we eat may be just as important as what we eat. Research in mice shows that TRF during their natural nocturnal feeding time promotes weight loss and prevents metabolic diseases when animals consume a high-fat diet. Similar research in humans has found that night-shift work (and, therefore, eating meals at night) is associated with obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Why does eating during the daytime seem to be so important to human health? Scientists think it's about disrupting circadian rhythms, our body's internal clock that responds to light and darkness and regulates tons of biological processes, like when we should sleep or eat. In modern society, they argue, artificial light and constant availability of food have interfered with our circadian rhythms, causing us to eat too frequently at unnatural intervals, possibly hurting our health in the process.

Lose twice as much weight with the new 2-day, low-carb diet!

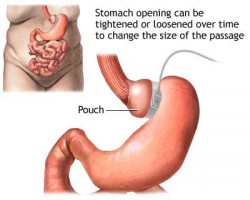

Chrononutrition's potential is exciting, but researchers say we can't draw any big conclusions yet. We know that messing with circadian rhythms can cause problems, but there's much more research to be done before we can reverse-engineer that link into a recommendation for when, exactly, humans should eat. (The solution for obesity and diabetes already exists. So why do so few people know about it?).

For now, we'll chalk it up as (time-restricted!) food for thought.